About a year and a half ago, I was sitting in my Manhattan studio apartment trying to write an html lexer in python. I was about half way through my batch at the Recurse Center, and I was frustrated with my lack of progress towards my learning goals and intimidated by all of the absurdly smart people around me.

While writing the lexer, I got hung up on an odd piece of python syntax.1 I spent “too long” trying to figure out what was going on with the sample code, and as a result, I felt even more frustrated by my lack of progress. I muttered a few curse words under my breath and then got ready to take another crack at my lexer code.

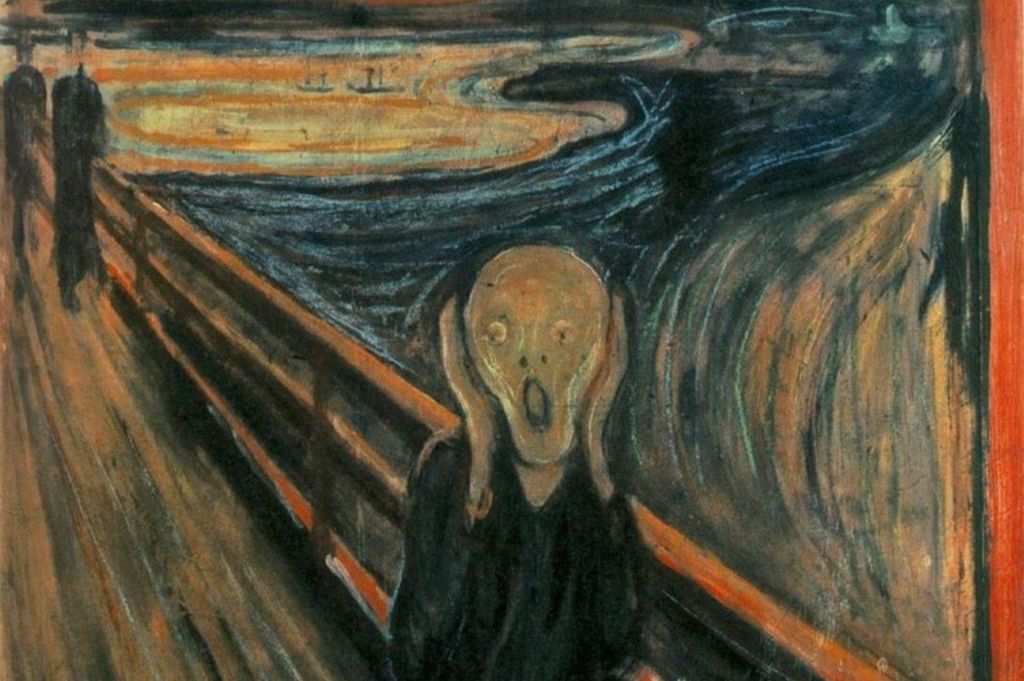

Then, just as I was thinking about about how to write my code, something happened that’s never happened to me before: My heart started racing; it felt like I was sprinting even though I just sitting in a chair. I felt short of breath and started sweating a bit. Then, after about a minute or so, the symptoms subsided.

☝ That was my first ever panic attack, and it freaked me out because I thought there might be something wrong with my heart. Prior to that panic attack, I’d been having chest pains for months, and I have some family history of heart issues. Fast forward a bunch of doctor’s visits, a hospital visit, and a few more panic attacks, and we found that my worry about my heart was merely another symptom of the anxiety itself. 😌

Of course, I was relieved to find out that I wasn’t dying or anything, but more interestingly, I was relieved to find out that I didn’t really need to make any deep changes in my behavior or thinking. I thought to myself,

“I can keep burning the midnight oil and the worst thing that’ll happen to me is a panic attack? Awesome. No problem. I don’t need to listen to people who are telling me I need to learn how to ’take it easy.’ I’ll just work myself up to the point where it feels like I’m going to freak out. Then I’ll take a break.”

Today, I completed my 1000th minute of meditation, and I know now that — and this probably seems obvious to you — my “work until you’re about to have a panic attack strategy” has some limitations. I’ve moved from panic attacks to yoga mats, and I want to share a bit about the journey.

From Panic attacks…

“Work until you’re about to have a panic attack” might obviously seem like a bad idea, but plenty of folks in silicon valley have said or presumed something like this at one point or another. Scott Galloway, an NYU Business professor and founder of L2, for example, advises:

On a regular basis, at work, demonstrate both your physical and mental strength – your grit. Work an eighty-hour week, be the calm one in face of stress, attack a big problem with sheer brute force and energy…At Morgan Stanley, the analysis pulled all-nighters weekly, and it didn’t kill us, but made us strong. This approach to work, however, as you get older, can in fact kill you. So do it early.2

Paul Graham, the founder of the incubator that’s produced billion dollar companies like Dropbox and AirBnb, basically defines a startup in such a way that working to your limit is essential for working at a startup.

Economically, you can think of a startup as a way to compress your whole working life into a few years. Instead of working at a low intensity for forty years, you work as hard as you possibly can for four.3

He goes on to say that a programmer working at a startup can create 3 million dollars of value per year (as opposed to the standard 80k you create working at a traditional company). To those who balk at the 3 million number, he says,

If $3 million a year seems high, remember that we’re talking about the limit case: the case where you not only have zero leisure time but indeed work so hard that you endanger your health.4

So the idea that startups are so hard that you have to work yourself to the limits of your health is pretty much accepted by lots of smart, experienced entrepreneurs, and partially because of this, I’ve basically accepted that working an a startup is extraordinarily grindy.5

I also think that the need for grinding hard is especially high for folks who want to be leaders at startups. Anecdotally, I’ve noticed that people don’t tend to work harder than their bosses (why should they?), and this intuitive idea is supported by a study or two that I’ve stumbled upon.6 If succeeding at a startup requires extraordinary effort from everyone in the organization and if people don’t work harder than their leaders, then leaders have to live the grind; they have to set the pace. 🏁 🏎️

…to Yoga Mats 🧘♂️

The move towards “yoga mats” started for me when I noticed that although I wasn’t working myself into having panic attacks, my anxiety and stress was leading to some extra intensity in my interactions at work. Eventually, I became convinced that this intensity made me less effective at leading.7 Here’s a couple of ways this has played out in the past:

-

I tried to convince some folks that we should not do X. We each stated our positions, and talked about it for a bit. As the conversation continued, I became more and more agitated that I wasn’t successfully convincing folks that we should not do X. The agitation was detected and people stopped taking me and my position seriously. Its like they said to themselves, “Matt is triggered. He’s not thinking clearly right now. His arguments can be safely ignored. Let’s do X,” and that’s a perfectly reasonable thought for folks to have.

-

I tried to convince some other folks that we should do Y. I said a bit about why I thought Y was a good idea and hoped the reasoning would stick. The problem, however, was that some folks thought the reasoning I gave was a smoke screen for something more “sinister” (read: company-oriented at the expense of employees). The impugning of my motives was no doubt partially a result of my anxious and intense stance towards work in general. People rightly worried that I don’t always have their best interests at heart. They’re right. Often this is because I’m too busy freaking out.

I did some research on this and it turns out that stress and anxiety messes with your ability to think clearly and to regulate your emotions much more than I had expected.8 So, by working through the anxiety instead of addressing it, I was trading off some short-term productivity gains for some big losses on how I communicated with people.9

After realizing I was making a bad trade off by not relaxing occasionally, I started trying to be calm by taking Sunday’s off completely. I followed everyone’s standard advice for relaxing: just do something you like doing that isn’t work.10 So, for a while, I mostly played League of Legends to “relax.” 🎮

A few weeks into this, I was playing one Sunday, hands tightly gripped around the mouse and cursing under my breath, and I thought, “Is this actually relaxing? It feels good and it’s fun, but is it actually going to help me be calm when it counts?” This question turned into a quest for how I could — and I get that this is weird quest — relax more efficiently. This is the quest that led me to start considering meditation seriously.

Although I was very skeptical of the effectiveness of meditation, it struck me as a potentially more efficient way of relaxing. Instead of losing my entire Sunday to gaming and other “relaxing” things, I could just set aside 10 minutes per day to meditate. Supposedly, 10 minutes a day is enough to have significant impacts on stress and anxiety levels.11

So, with a healthy dose of skepticism, I decided to give meditation a try for a bit by using the Headspace app, and so far, I think the results have been pretty positive:

- I haven’t had any anxiety-related chest pain or GERD since I started.

- I’ve been more aware of some unhelpful patterns of thought I tend to fall into, patterns which tend to waste time and produce more anxiety.

- There’s been a few moments where I felt that I would have ordinarily interacted with others with more intensity and instead found myself simply anticipating and watching my intense emotions dissipate instead of actin’ a fool.

- My daily meditation habit has also helped “bootstrap” other helpful habits.12

In addition to these “in the field benefits,” the experience of meditating is surprisingly and uniquely refreshing. Two things stand out from the experience:

-

Occasionally, after a 10 minute session, my body feels extremely relaxed. I can tell that some of the tension I ordinarily carry around in my body has been released. My arms feel completely dead, resting on my lap. My mind also feels remarkably clear and I feel like I can focus on what needs to be done for the day.

-

Occasionally, during the “focus on your breath” part of the exercises, I sometimes slip into a state where it actually feels like my mind is resting. Ordinarily, my mind is constantly running, thinking about myself and the past and the future. In these moments, however, I feel “present” and I’m not thinking about anything else except my breath. It feels great.

I’ve read a bit about the changes that happen to the brain during meditation, and apparently, there’s a set of regions in the brain called “the default mode network.” 🧠 Judson Brewer, a psychiatrist whose been scientifically studying and practicing meditation for decades, calls this region the “narrative network” of the brain because its the part that is always telling a story about our past, our future, our successes, and our failures.13 This region, according to his research, is less active during meditation and his research lines up exactly with my experience of meditation, which is reassuring because like I said, I approached meditation with a lot of skepticism.

Footnotes

-

It was probably a list comprehension, but I can’t remember for sure. ↩︎

-

The Four: The Hidden DNA of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google, pg. 252. ↩︎

-

“How to Make Wealth.” Interestingly, I happened to notice Paul Graham’s “Mean People Fail” essay while digging up this quote, and it is precisely this claim that drove me to ease up on the “work until you endanger your health” attitude. ↩︎

-

Ibid. I get that working so hard you “endanger your health” is the limit case for Graham, but its the limit that we must strive for, according to Graham. ↩︎

-

I think that DHH opposes the idea that startups require this kind of hard work, so he might be an exception here. He points to 37 signals as a counter-example, but I think this is problematic for several reasons. First, 37 Signals is not a startup since startups are characterized by their rapid growth and 37 Signals is intentionally not growing quickly. Second, even if 37 Signals is a startup, their success could be an anomaly. This is not to say that they didn’t work hard, but it might be that they lucked out insofar as they were able to succeed in spite of their lack of willingness to grind as hard as other startups. To point to them as a model to follow is as wise as advising Bob to by a lottery ticket because Billy just won. ↩︎

-

One study was buried in an HBR article that I can’t find right now. Basically, the study pointed out that workers’ email communication outside of standard work hours mirrors the email patterns of their supervisor. ↩︎

-

This realization took an embarrassingly long time. I used to excuse my “intense” attitude and not-always-mild assholery by pointing to entrepreneurs who have managed to be successful with these attitudes, entrepreneurs like Jobs, Bezos, and Musk. Two problems here: 1) I’m not nearly as brilliant as these people. I think people are more forgiving of assholery if you’re a genius. 2) Even if these guys managed to be successful, that doesn’t mean that they’re successful because of their attitudes. ↩︎

-

“The Stressed Brain” by Rajita Sinha was really solid here. ↩︎

-

I actually think this matters a lot less for people who aren’t aspiring leaders. Interestingly, a lot of the examples that I’ve seen about how grindy things can be at startups seems to focus around individual contributors. We definitely see this in Paul Graham’s example. Its about a programmer who’s just trying to grind out some code. Doesn’t really matter if he gets pissed at his computer in the process. The hbr article I stumbled across a few weeks ago about how executives tend to get more sleep than individual contributors also points in this direction. ↩︎

-

“Do something that’s not work” as advice for relaxation presumes a certain view about the relationship between work and life. This is the same view that’s presumed by the phrase “work-life balance,” and it turns out that this view has been called into question by I/O Psychologists. More specifically, in Psychologically Healthy Workplaces Larissa K. Barber, Matthew J. Grawitch, and Patrick W. say, “Eikhof, Warhusrt, and Haunschild (2007) noted a number of assumptions in the work-life balance literature, such as the notion that the work domain is the source of the problem…and that the work domain should be separated from the nonwork domain (work-life integration is stressful). All of these assumptions overlook contradictory evidence showing that many individuals derive enjoyment and personal meaning from their work (Wrzeniewski, LoBuglio, Dutton, and Berg, 2013; Wrzesniewski, McCauley, Rozin and Schwarts, 1997)…” ↩︎

-

I believe this is mentioned in “The Stressed Brain” video, but its also mentioned in this TED talk and in this HBR article. ↩︎

-

I’m not sure if its the meditation habit itself that’s doing the work here. Stress and anxiety compromise the executive functioning of the brain, so it might be that the stress reduction that results from meditation has improved my executive functioning, which in turn has made space for me to adopt other helpful habits. ↩︎

-

Judson Brewer, The Craving Mind, xvi. ↩︎