Product managers have to make bets on the future. If you think for a few seconds about the types of risk that product managers are charged with managing, this becomes obvious. Product managers — as Marty Cagan points out — must manage risk around:

- value risk (whether customers will buy it or users will choose to use it)

- usability risk (whether users can figure out how to use it)

- feasibility risk (whether our engineers can build what we need with the time, skills and technology we have)

- business viability risk (whether this solution also works for the various aspects of our business)

All of these require some betting on the future, but managing value risk and business viability risk in particular require forecasting that can be especially difficult to do. Managing these risks requires good forecasts on how much profit will be generated by a product or a product change, and doing that requires good bets on how much it’ll take to acquire a customer and how much more revenue a customer will generate once a new solution has been built.

This kind of forecasting is tricky business, and despite it’s importance in good product management, it’s not something that I’ve ever seen discussed or tracked seriously. Unfortunately, good product managers appear to be “identified” by “pedigree,” which is problematic because sometimes we can fooled by luck about how good a product manager’s judgment really is about where a product needs to go.

If you’ve paid any attention to Daniel Kahneman (Thinking Fast and Slow) or Phillip Tetlock (Superforecasting) or Shane Farnish (Farnam Street), you’ll be familiar with this idea. Forecasts made by product managers aren’t very different from forecasts made by people in general: there’s a lot of grand pronouncements without any serious thinking about how to know whether those pronouncements are worth anything.

I want to see if we can do better than this, but we can’t know the limits and potential utility of product management related forecasting a priori. That’s why I want to kick off what I’m calling the “Cassandra project.”

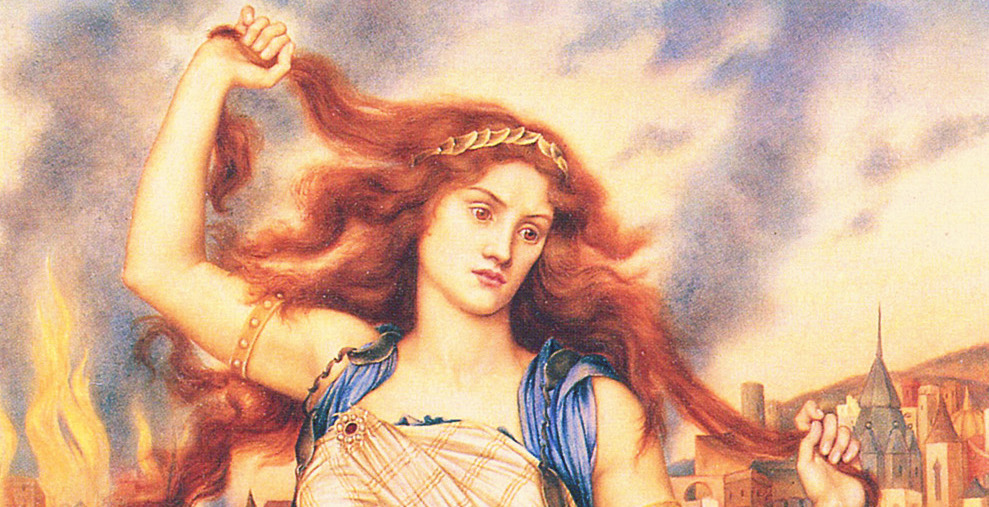

Cassandra (depicted above) was a seer from Greek mythology who saw the burning of Troy before it happened. Good PMs should work towards Cassandrian-like insight into the future. Cassandrian insight helps companies avoid “burning Troy’s,” the avoidance of the disaster of wasted resources on a product doomed to failure from the start.

We can’t become better forecasters without practice and feedback on our forecasts. So, the Cassandra project is an attempt to measure the quality of product management related forecasts over time. Even if the only reasonable conclusion after measuring forecasts over time is that PM’s don’t have much insight into the future, that conclusion would bring some appropriate humility to a role that is plagued by arrogance.

An Example

So how will this work? In his research on forecasting, Tetlock uses Brier scores to assess the quality of forecasts. We can do the same thing. Calculating a brier score is fairly trivial, so I’m not going to get into the details here. (The wikipedia article on Brier scores is helpful.)

Metric for measuring forecasts? Check. The next thing we need are forecasts we can make fairly regularly.

Revenue forecasts tied to specific products at public companies are a good candidate. Apple, for example, releases revenue tied to the iPhone every quarter in their 10-Q. New features from apple products are very public, so we can try to guess at how the new features and iterations of the iPhone will impact Apple’s revenue for a particular product.

We already do this sort of thing. We watch WWDC events. We comment on how great/dumb the touch bar is on the new macbook. We guess at how that’ll affect macbook sales.

But with Brier scores and a public record of forecasts, we can be more objective about how good our forecasts are. We can ask, for example:

How likely is it that Apple’s iphone-related revenue will grow faster than last quarter?

And we can answer by looking at the previous quarter’s data and by thinking about new features/hardware and guess:

50%

And the following quarter we can see how good our forecast was. Let’s say iphone-related revenue did grow faster. In that case, we’d have a Brier score of: .25. Brier scores are like golf scores: lower is better. God-like forecasting skill means you’d get a brier score of 0.

How to participate

If you just want to see how I’m doing, use this link.

However, this’ll be more interesting and useful if I don’t have to think of all the questions and if I’m not the only one playing. So, I’d love it others participated. For now, the only way to do this will be via github. You can make your own forecasts and propose questions by submitting a PR on github. You’re forecasts will show once the pr has been approved and merged.

I’ll consider building a more accessible and robust way of participating if there’s enough interest.

Forecasts

Will the percent change in iPhone revenue growth from Q1 2018 to Q1 2019 be greater than the percent change in revenue growth from Q4 2017 to Q4 2018?

Looking at Apple’s 10-Qs, it seems that they are fond of comparing iPhone sales during the quarter to sales during that same quarter in the previous year. (Guessing this is because sales vary according to seasons). That’s why the above question is about changes in change percentage between the reported quarter and that same quarter the previous year.

According to the most recent 10-Q, the percent change in revenue growth from Q4 2017 to Q4 2018 was -15%.

| Name | Forecast | Score (available in May) |

|---|---|---|

| Matt Dupree | .25 | |

| Your name | your forecast | your score |

10-Qs are here.