Imagine for a moment that there’s an annoying fly buzzing around your guests at a BBQ you’re hosting. You and your guests swat at it a few times, but no one manages to nail the sucker. You run into the house to grab a fly swatter, but you find that even if you wait for the fly to settle down somewhere, you can’t quite smash it.

Frustrated and desperate, you decide to evacuate the party (and the state), get your hands on a nuke, and nuke the fly along with your backyard and neighborhood. Watching the mushroom cloud form from your fallout shelter, you raise glasses with your guests and say, “we got’em boys. Good work.”

Obviously, this is an absurd story. I’m telling this brief absurd story because there are parallels between singletons as a data loading solution and nukes as a fly swatter. Singletons for data loading, like nukes, are hard to test, leave a mess behind them, and are overkill. These parallels are the reasons that I try to avoid using singletons for data loading on Android. That’s what this post is about.

The Fly: Data Loading in Activities

Before I dive into the reasons I try to avoid singletons for data loading in Activities, I want to clearly state the problem for which I think singletons are poorly suited.

Here’s the problem:

Activitys are destroyed and re-created on configuration changes.- If we’ve performed an expensive operation to get the data displayed by that

Activity, we’ll want a way for the results of long-running operations to be cached across orientation changes. - If we need to perform an expensive operation to get data, the results of this operation must be held if there’s a configuration change while the operation is being performed and delivered once the

Activityhas been re-created after the configuration change.

I think singletons are a sub-optimal solution for this specific problem. This is not a post about why singletons are bad, full stop. Let’s move on to why I think this.

Hard to Test

Fortunately, nukes are hard to test. You’ve got to find a large area that you can pollute with radiation, and, depending on your place in the world order, you need to be prepared to handle varying degrees of fallout from the international community.

Unfortunately, singletons are also hard to test, and this counts as one strike against them as a data loading solution in my mind. Others have already noted in detail why testing with singletons is hard,1 but let’s look at a brief example to see why testing with singletons is hard.

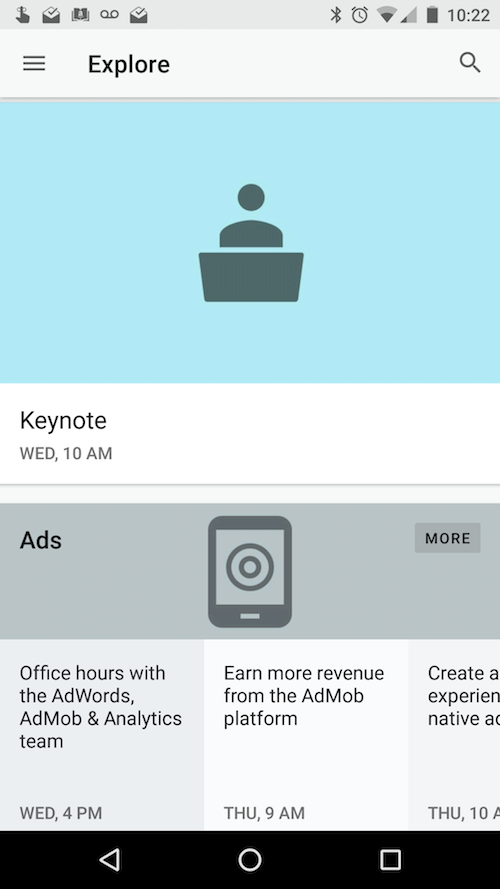

Let’s say you’re tasked with implementing a screen that loads data from a database like the explore sessions screen from the google I/O app:

Because the fairly complicated logic governing whether the list of sessions should be preceded by various preference cards scares you a little, you decide to write tests for this screen. Since you know you’re not going to have an easy time testing logic in an Activity, you move the logic to a presenter:

public class SessionsPresenter {

//...

void present() {

if (shouldShowSessionNotificationsCard()) {

sessionsView.showSessionNotificationsCard();

}

if (shouldShowConferenceMessagesCard()) {

sessionsView.showConferenceMessagesCard();

}

SessionsStore.getInstance()

.loadSessions(new SessionsStore.LoadCompleteListener() {

@Override public void onLoadComplete(List<Session> sessions) {

if (sessions.isEmpty()) {

sessionsView.showNoSessions();

} else {

sessionsView.showSessions(sessions);

}

}

});

}

}In the first highlighted line, we’re accessing a singleton to load the sessions. In the following highlighted lines, we either show the sessions or something indicating that there are no sessions at this time.

The use of a singleton in this code makes this presenter difficult to test. When we’re writing a test for SessionsPresenter, we need to be able to swap out the implementation of SessionsStore with stubs that will return canned responses so that we can execute each branch of the if-statement highlighted above. This is not easy with a singleton in place.

Getting around this problem forces us to create additional methods that are only used by the tests. For example, to test the above code, we’d need to add SessionStore.setTestInstance and set the test instance with a stub during our unit test:

public class SessionsPresenterTests {

//...

@Test public void showsNoSessionsViewWhenNoSessions() {

//...

SessionsStore.setTestInstance(new SessionsStore() {

@Override

public void loadSessions(SessionsStore.LoadCompleteListener listener) {

listener.onLoadComplete(Collections.emptyList());

}

});

//...

}

}When we need to change the API of the SUT solely2 for the purpose of testing, our tests are telling us there’s a problem with our design.

Even with these added methods, however, we lose the ability to speed up our tests by running them in parallel.3 The likelihood that tests are run regularly is related to how long it takes to run them. Tests are often more likely to be useful the more often they are run, so placing an unneeded limit on how quickly our tests can run is not ideal.

At this point, some readers may point out that these problems are alleviated if we inject the singleton through the constructor and if we keep our Activity as a dumb view that isn’t scary enough to test. The code for this suggestion might look something like this:

public class SessionsActivity extends Activity {

@Override public void onCreate(Bundle bundle) {

super.onCreate(bundle);

new SessionsPresenter(SessionStore.getInstance()).present();

}

}This does alleviate the testing problems at the unit level. However, if we want to stub out what gets returned by the singleton SessionStore for UI tests, we’ll still have to add a SessionStore.setTestInstance method. Again, modifying the API of our classes for testing purposes is smelly.

If you’re using a @Singleton-scoped dependency that you inject with dagger, then we can facilitate UI testing without adding a setTestInstance method. This is the best version of the idea of using singletons for loading data in Activitys. Even if I didn’t mind the fact that including dagger was a high price to pay for doing any data loading in an Android app, I still wouldn’t ever feel comfortable using @Singleton-scoped dependencies for data loading for the following reasons.

Leaves a mess behind them

Data owned by your singleton will live for the entire process, unless you do something to clean it up. We’re often worried about memory on Android devices. Even if our app performs fairly well on devices with low-memory, irresponsible use of memory can lead to a sort of tragedy of the commons, where the user experience suffers overall.

Chet Haase in Developing for Android captures this well:

if any of these apps consume more memory than they need to, then there will be less system memory left over for the others. When that happens, the system will evict app processes (shutting them down), forcing the user into a situation where apps are constantly re-launching when the user switches to them because they cannot stay present in the background due to memory pressure.

So overall: use as little memory as you can, because the entire system suffers if you don’t.

If our apps are going to be good citizens on user’s devices, we ought to clean up the data owned by our singleton once we’re done using it. Singletons for loading data, along with the memory concerns on Android, place an extra burden on us as programmers. Strike two for singletons.

I can imagine cases and apps where the memory issue isn’t a big deal. I work at a company where the minimum API level for our app is 20, so we definitely have less performance concerns than other companies. In cases where the data held by singletons really isn’t cause for concern, I could just never clean up the data held by the singleton, which definitely makes working with them easier. Still, there’s another reason I try to avoid singleton’s for data loading.

Overkill

Nuking a fly is absurd because its overkill. You just want to kill the fly. You don’t mean to obliterate the 3 mile radius around the fly.

Similarly, singletons are overkill. We don’t really need the data loaded for our Activity to live for the entire process. This is precisely why we usually have to clean up some of the data when the Activity is done using it.

Often what we really want is data that is cached across configuration changes, but the fact that the cached data within a singleton lives for the entire process makes implementing our retrieval of that data more complicated. Let me explain why.

Suppose I want to want to send two emails with two different attachments. Both times I go to attach an email, the same type of Activity will be launched. Suppose this Activity gets its data from a singleton-based data loader. If both of these Activitys try to grab data from the Singleton, the user can wind up with stale data the second time they try to attach an email because the first Activity has already populated the cache with data that was fresh at the time the first Activity asked for it.

Of course, these are solvable problems. However, I think it’d be better if we didn’t have these problems in the first place. It turns out there’s already a solution for data loading that doesn’t have any of these problems/complications.

Loaders: A Professional Fly Swatter

Loaders are designed for this exact problem. They don’t “overkill” by giving us data that lasts the entire process instead of what we need: data that survives configuration changes. Because of this, there’s no need for us to worry about stale data when multiple Activitiys need the same data. Moreover, we don’t have to worry about cleaning up data once its no long used. Finally, if we use them sensibly, Loaders don’t pose any special challenges to testing.

I’m not denying that it can be difficult to get a handle on how Loaders work. Nor am I saying that their API is a joy to work with. However, I think trudging through the docs and/or wrapping the Loader API in something more usable (e.g., RxLoader) is the best option we have.

The alternative is to use singletons for data loading in our Activitys, which, if you buy into my argument and analogy is silly for the same reason it’s silly to nuke a fly at a BBQ you’re hosting.

Notes:

-

Misko Hevery, “father of AngularJS,” has a really nice explanation of the relationship between singletons and testing as a part of his testing guide here.

-

“Soley” is emphasized because otherwise the statement might feel like a contradiction. I’ve been saying recently that tests force us to design better applications, so how can it be that there’s a problem if the tests make us change the API of the SUT? There’s no problem the if we change the API of our classes to support testing, as long as that change introduces flexibility that can be used both by the application and by the tests. A

setTestInstancemethod, as the name implies, is only used by tests. This seems like a sensible way of resolving the contradiction, but honestly, I need to think about this more to be sure. -

Ibid.