Edit: In the post that concludes this series, I point out that making unit testable Android apps does not require us to remove compile-time dependencies on the Android SDK and that attempting to do so is impractical anyway. Ignore anything in this post that suggests otherwise.

Unit testing your Android apps can be extremely difficult. As I suggested in the introduction to this series, it seems clear that there’s widespread agreement on this. The many folks who responded to my introductory post, moreover, seemed to reinforce my claim that Android unit testing is tough:

So, Android unit testing is hard. That much is clear. Why Android unit testing is so difficult, however, is less clear. Its true that a part of the difficulty with Android unit testing has to do with the nonsense that you have to overcome to get Roboletric started so that you can run your tests at a decent speed, but I think that there’s a deeper reason why we are having a hard time testing our applications: the way that Google has written the Android SDK and the way that Google encourages us to structure our applications makes testing difficult and, in some cases, impossible.

I realize that this is a bold claim, so I will spend the entire post trying to establish it. In the following post, I’ll try to say more about how the “standard” way of developing Android applications encourages us to write code that is difficult/impossible to write sensible unit tests against. These posts are a part of a series in which I’m exploring the viability of enhancing the testability of Android applications by restructuring them so that application code does not directly depend on the Android SDK. Showing why the standard architecture for Android development makes testing difficult will both motivate and inform my alternative proposal for structuring Android applications, a proposal that I will outline in the fourth post of the series.

A (Seemingly) Simple Test Case

To see why unit testing in Android is so difficult, let’s start by looking at a simple test case. I’ll be using source code from Google’s IOsched app because, as I pointed out in my first post, that app is supposed to serve as a model for Android developers.

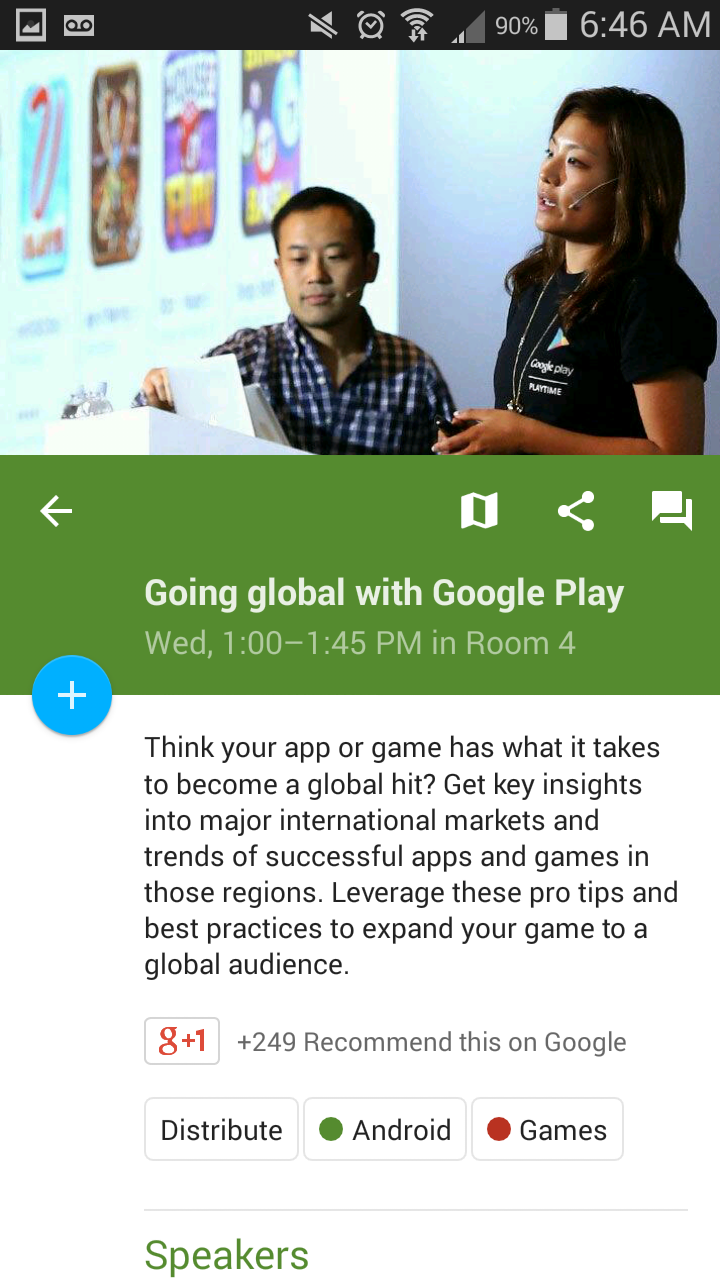

The IOsched app has a IO session detail screen that looks like this:

Notice that the detail screen has a “+” button that allows users to add the session to their calendar. That plus button turns to a “check” button if they’ve added the session to their calendar. If they tap the “check” button again, the session will be removed from their calendar. The state of the button is (confusingly) stored in an instance variable called mStarred, so depending on the state of this button, the Activity will launch a Service that adds or removes that session to the user’s calendar in its onStop() method:

This seems like a sensible piece of code to write a unit test against. Here’s the problem: you can’t write a unit test against this code. In order to see why, we’ll have to take a step back from Android and think a bit about what makes code testable in general.

The three steps of a unit test, as we all know, are arrange, act, and assert. In order to successfully perform the assert-step in our test, we need access to the state of our program that was changed as a result of the code executed in the act-step of the test. Let’s call this state the “post-act-state.” For unit tests, there’s only three ways that we can access the post-act-state.

The first way we can access the post-act-state is to check the return value of the method that executed during the act-step of the test. Writing tests against these methods is easy:

The second way to get a handle on your post-act-state is to get a reference to some publicly accessible property of the object being tested, and to assert that the state of that property is what you expect:

The final way to assert that your post-act-state meets your expectations is check the state of the object’s injected dependencies. These dependencies may not be publicly accessible, but because you inject them during your test method, you have a reference to them:

Now that we’ve listed all of the ways that we can complete the assert-step of a unit test, we’re in a position to see why the above Android code is untestable: there’s simply no way for us to complete the assert-step of a unit test against the onStop() method. onStop() doesn’t have a return value. There’s no publicly accessible property of SessionDetailActivity that will help us verify that the SessionCalendarService has been launched with the correct instructions. Finally, the code that launches the SessionCalendarService is not code that belongs to a dependency that’s been injected into SessionDetailActivity.

Unfortunately, it gets worse than this. It is also impossible to complete the arrange-step of a unit-test for onStop(). In order to complete the arrange-step of a unit test, you must be able to alter any conditions that affect the post-act-state of your program. I will call these conditions “pre-act-state.” Since there’s no way to change the pre-act-state for onStop(), we can’t unit test it.

The pre-act-state within onStop() is the mInitStarred boolean. Again, here’s the source for onStop():

This boolean is set in a callback method that’s executed after a ContentProvider query has completed:

There’s a reason mInitStarred is initialized in a Loader callback. If a user adds a session to their calendar and navigates away from the SesssionDetailActivity, the flag indicating whether the session is a part of a user’s calendar is stored in a database table containing IO Sessions. As we all know, Google wants us to use Loaders to get data from a database, so mInitStarred gets initialized in a Loader callback.¹

mInitStarred is used to determine whether its actually necessary to launch a SessionCalendarService to update the user’s calendar to include or exclude a particular session. If the database tells us that a session is already a part of a user’s calendar and if the state of the plus button indicates that that’s what the user wants when they leave the SessionDetailActivity, then we don’t need to do anything.

So, if we’re testing onStop(), we want to make sure that it launches a Service that updates the user’s calendar according to the state of the plus button only if necessary. Unfortunately, because mInitStarred is a private instance variable that’s initialized in a Loader callback, there is simply no way for us to change the value of mInitStarred from a unit test method. Again, to see this, let’s think through the ways that we alter an object’s pre-act-state state for a unit test.

The first way is to alter a publicly accessible property that affects the object’s pre-act-state:²

The second way is to change the parameters passed in to the method being tested:

Again, neither of these two options are available to us, so we can’t even complete the arrange-step of a unit test for onStop(). There is no publicly accessible property on SeessionDetailActivity that we can set to alter the value of mInitStarred. onStop(), moreover, doesn’t take mInitStarred as a parameter, so we can’t modify the pre-act-state by changing onStop()’s parameter value either.

Conclusion

So, a piece of code that seems like it should be easy to unit test, turns out to be impossible to test. If you’ve ever found yourself staring at Activity for hours trying to figure how to unit test some of its business logic, this is why: In many cases, it’s just not possible. It some cases, it may be impossible to complete the arrange-step of a test because you have no way of altering the test object’s pre-act-state. In other cases, you may not be able to complete the assert-step of your test because you can’t access relevant post-act-state. onStop() in SessionDetailActivity suffers from both of these problems.

There is plenty of Android code that is simply untestable. I think that the way we structure our applications, along with some special properties of Android platform, set us on a path to writing un-testable code. In the next post, I’ll elaborate on this claim.

Against Android Unit Tests:

- Introduction

- Why Android Unit Testing is so Hard: part 1, part 2

- How to Make Our Android Apps Unit Testable: part 1, part 2

- Quick Summary

- Conclusion

- Followup: Summary

- Followup: Unit Testing Dynamically Constructed Views

- Followup: Testing in Android Studio 1.2

Notes:

-

They push Loaders pretty hard in one of their videos for the Udacity course on Android Development.

-

Clearly there’s multiple ways of doing this. If, for example, the pre-act-state is determined by a dependency of the object being tested, we can also modify pre-act-state by changing the dependency’s public property.